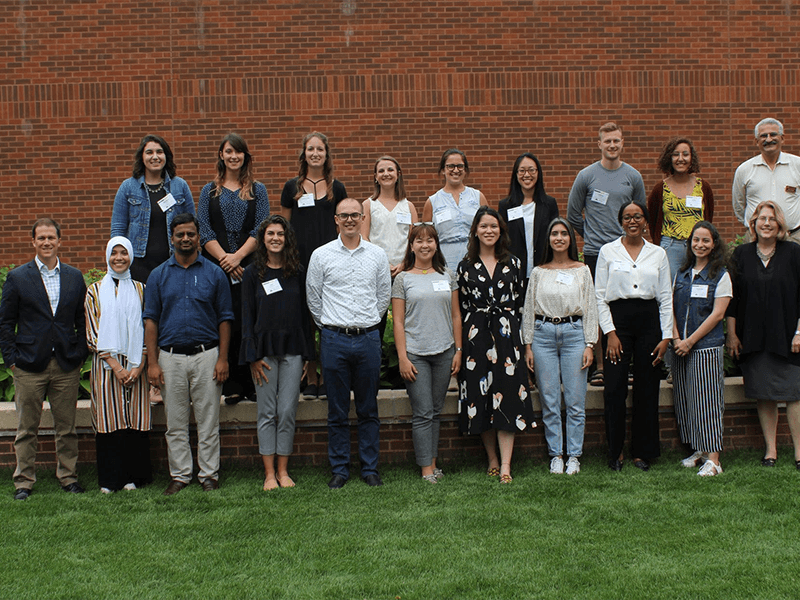

In part 1 of this, we look at the Yousriya Loza-Sawaris Scholarship program we introduced six scholars, their backgrounds, and what they advise in terms of handling the demands of the Master of Development Practice program (MDP) at the University of Minnesota. This part 2 examines the MDP experience more closely along with the scholars’ post-graduation directions.

Oriented to Reality

The MDP centers on a summer-long field experience between the first and second year of study in which teams of students travel to tackle a real world client project. Other classes and the program’s concluding capstone project also often involve real world efforts and evaluations.

The practice-based nature of the MDP was frequently mentioned by the scholars. “I needed more on applications, the real world side of things,” Sara Ragab Hussien, a first-year YLSS scholar, says. The MDP “captured my attention.”

Nayera ElHusseiny, a past scholar, at first shied away from the MDP because of its two-year length. “I knew I did not want to be gone away from the practical reality of social development for too long,” she remembers. “I knew there was a big gap between practice and academia. But this was before I found out how practical and hands-on the MDP program was…..No thesis, lots of projects in Minneapolis and around the world. I was sold on the idea.”

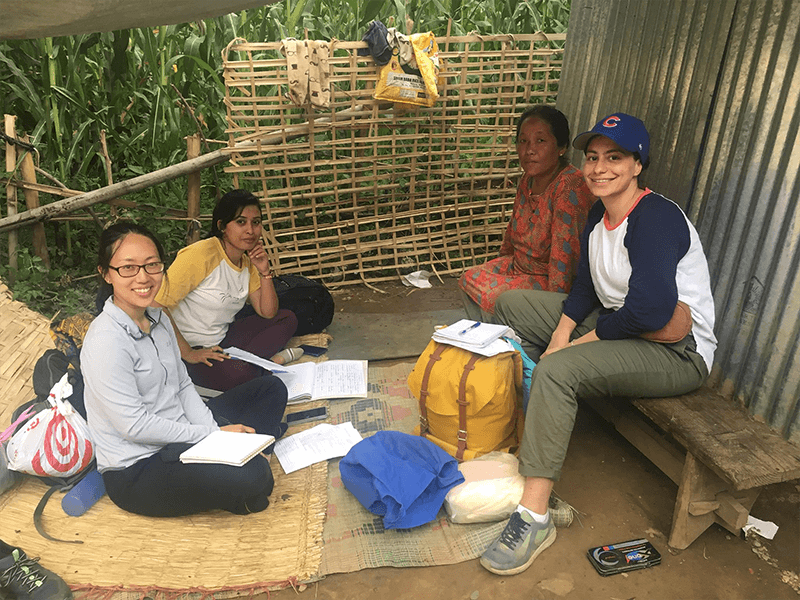

2 of the YLSS scholars, cohort 3 – Conducting Focus group discussion during their summer internship in Nepal with Rural Nepali women to know more about their small enterprises.

“I was very cautious going into the program,” she continues. “I expected I was probably going to hear a lot of things far removed from reality, not parallel to what I saw in Cairo but it was the exact opposite. My MDP cohort was from all around the world, not just American but more international students, all with very keen practical skills, a lot of experience, knowledge we shared all the time,” with multiple groups collaborating in each class each week.”99 percent of people were very reality oriented, very practically oriented.”

Yasmine Hesham Mansour, a second-year student, on the other hand, was originally looking for academic knowledge of development to back up her work experience in Egypt. “The MDP was a perfect chance for me because it’s both practical and academic,” she says. “I felt I’m going to get international experience and at the same time backed up with academic knowledge.”

In addition to its mix of the practical and academic first-year scholar Neamatallah ElSayed was drawn to the MDP’s field experience. A program focus that involved “traveling to countries other than the U.S.” promised broad exposure and growth.

In the Field

“In the first year projects were designed to prepare us for the field experience,” says Nayera. “In the second year, we reflected on what designed during the experience and what we want to change.”

Yasmine also found the summer field experience transformative. “The subjects did not seem really connected until we went to the field, and then everything made sense.”

“Most things you learn in class you don’t really appreciate until you go into the field and work on actual projects,” echoes second-year student Sara Zagloul. “This professor would say ‘I know it sounds simple to you but when you go into the field you will use it.'” And that proved true for many different classes. “When we went into the field, the program came into play. We saw through a different lens and appreciated every single word!”

Her team’s field experience, in Indonesia, involved evaluating training for a local cooperative and large nonprofit producing timber using certified, sustainable methods. This focus quickly shifted to working with the cooperative on a market analysis and value analysis. “We each had experience with international projects but were not so familiar with this,” says Sara, describing her prior knowledge of Indonesia as “minimal.”

The MDP team is traveling for five hours in Nepal to reach a remote rural village to interview rural women and find innovative ways to support their small enterprises.

They negotiated everything from accommodations and hiring a translator to transcribing surveys to be given to farmers and managing “presentations in English for people who didn’t speak English.” Sara does not expect such an opportunity again and while “it was hard to go through,” she appreciates it. “I learned a lot. It’s something that is going to stick with me a very long time,” she says.

Nayera also worked with sustainable timber, but in Kenya, creating a needs assessment and value chain map for a company interested in expanding to a different part of the country. “We covered 11 cities, 250 interviews, farmers, wood market vendors, factories, government officials,” she ticks off. “There were a lot of productive challenges, we had to revise all our data collection tools to be more appropriate to client needs, priorities of farmers….” The goal as she describes it was “to stay true to the voices in the field but also to take something useful and package it for the client. It was just a very amazing experience in all aspects.”

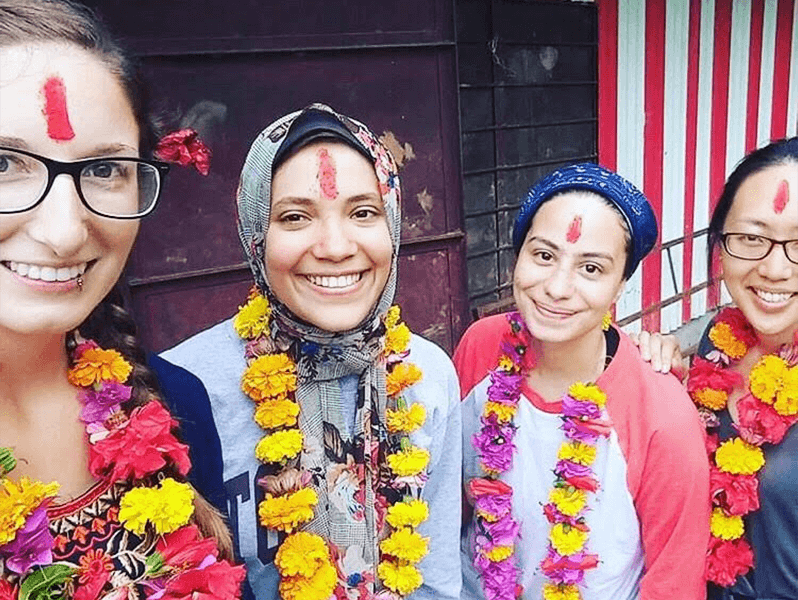

The Nepali community welcomes the MDP team and their advisor Dean Current with flowers and colorful scarfs.

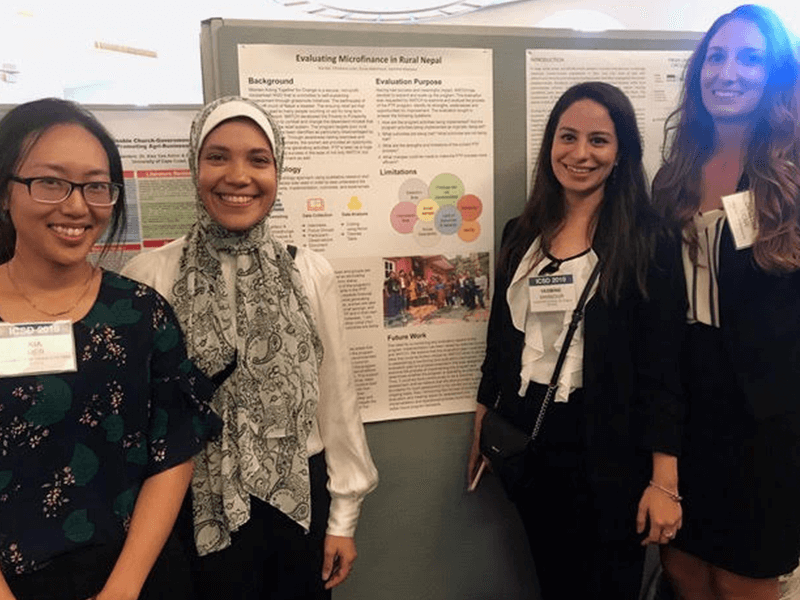

During Yasmine’s field experience in Nepal, the client organization “didn’t like our evaluation plan. We’d been taught to be be flexible to people’s needs and after our pilot they thought we were changing everything. There were many cultural barriers between us and the client.” The project, which focused on evaluating a poverty alleviation program for rural women was also “hard physically [with hours-long walks from village to village] and emotionally.” She nonetheless values the experience and lessons learned, for instance “to better communicate our plans and needs in first meetings with any clients.”

Mohamed Fouad, one of the first YLSS alumni, had an atypical summer field experience. With a choice of six projects in six countries, he decided to return to Egypt to create a monitoring and evaluation system, involving hands-on project application as well as design. Generally the field experience is a team project but there was a security alert for Egypt and his team mate dropped out. For his final capstone project, Mohamed traveled with five team mates to Guatemala where a pilot as taking place transferring management of national parks from the government to the tribes who own them and live there. They began set up for an Excel system to perform varied functions from generating tickets to marketing services to human resource and financial management. “It’s satisfying to work on something like that,” he says.

MDP Takeaways

Asked what she gained from the MDP program, Yasmine responds. “My self-confidence became much, much better,” she says. “Two years ago I wouldn’t speak like I’m speaking right now.”

“Confidence,” agrees Sara Ragab, “Since the orientation, we’ve really focused on how to present ourselves…. The other thing is…reflecting on your goals and making sure on you’re on the right path, and at the same time being able to adapt and able to work under uncertainties like the conditions we are under right now [with the coronavirus crisis]. This is what working in development is about, you don’t have a clear path forward, you have to keep adjusting, reflecting, being resilient, moving forward.”

“My self-confidence became much, much better,” says Yasmine. “Two years ago I wouldn’t speak like I’m speaking right now.”

“Our professors showed us the ugly side of development,” says Yasmine. “They want us to appreciate this ugly side and that it’s not a perfect world but at the same time you can change people’s lives. Corruption is everywhere, politics is everywhere. Acknowledging it exists is a great asset.”

“At first I questioned myself,” Yasmine continues. “‘why am I here, why am I studying? I want to help people!’ But it’s an asset to acknowledge this [ugly side]; you just have to make use of it in the interest of people.”

“You come into development thinking it’s this utopian thing,” says Sara Zagloul, “but there are so many layers we didn’t see because we didn’t study it, you only saw the outer layer.”

The program “gave me tools to find answers from the communities themselves,” says Nayera. “It completely changed my perspective on how social development planning should be designed, from the bottom-up [rather than the top-down]….to see whether we can add value or might do more harm than good. That was my key takeaway.”

Plans and Careers

Yasmine is applying for jobs and hopes to pursue a career “related to poverty alleviation and economic empowerment, or with Syrian refugees since I worked with them before and liked it. I don’t think I’ll pursue a Ph.D. or a second master’s. I’m trying for jobs that have impact. I want to work in the field….If I can gain a job empowering people, I will have used the scholarship not only to have better understanding or a better salary but I will be able to help vulnerable groups more than I could before.”

Sara Zagloul wants to specialize in “urban development, energy sustainability. I would love to work in disaster mitigation,” she says, “but I think it’s not really established as a field in Egypt much yet–though we have lots of disasters,” she laughs.

Sara Ragab is less certain. “The more classes I take, the more my interests are constantly changing. I could say something now but by next year it could completely transform. Development is very large….I like it all but am not sure what I’m going to specialize in.”

Neamatallah has thought she would go back to work for the government but also finds her interests “constantly changing.” A particular interest at present is “the intersection between gender and poverty.”

Nayera has returned to the Sawiris Foundation to work as an officer in its Learning and Strategy sector, which she has been able to shape from a brand-new unit. “It just started the same week I joined the foundation, the process of building a monitoring and evaluation system. Coordinating templates and work plans, what kind of data, who will be doing what, working with NGOs and capacity building, working with partners we fund, project management.”

“The angle felt right after the MDP program,” she says. “I work a lot with evaluators….the MDP program has equipped me with language and technology to speak and engage with the evaluators in a productive way.”

Mohamed’s bank had allowed him to attend the MDP program on a leave of absence, but when he returned there he discovered he no longer wanted to be a banker. “I really wanted to work in the development field,” he explains, and after three months he accepted a position as Deputy Managing Director for ENID (the Egyptian Network for Integrated Development), which he has held ever since. He’s involved in a range of work for the organization: “finance, project planning, HR, supervising daily work for every department, writing proposals for donors, reports for donors, a lot….great experience.”

“We work with people, and find solutions. Every day I work with a new social problem,” he continues. He gives one recent example: “We developed an idea to make face masks to fill a shortage. Here in Qena, our capital, there’s a small factory, a workshop with sewing machines already…we thought we could use these machines to make these masks, and we have started that. We have an agreement with the governor of Qena and they are actually using these masks. Something local but it has a cheap price and people cannot find medical masks everywhere. So it’s a great service….we will prevent coronavirus as much as we can.”